Modes

The Diatonic Scale

The Diatonic Scale

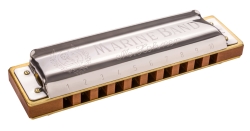

Imagine you were given a piano with no black keys. You could still produce a familiar do re mi scale and plenty of melodies using the key of C major, as this doesn’t require the sharps or flats of the black keys. Your white keyboard would effectively be a C diatonic keyboard, offering up the notes of the C major scale in each direction from Middle C. The notes of the C major scale are C D E F G A B and C again. That’s an eight note sequence, or octave. And it’s exactly what’s in our 10 hole diatonic C harp between holes 4 and 7. Try it for yourself 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B. These are our melody, or soloing, notes.

The Chromatic Scale

If we reintroduced the black keys to our piano, it would become a chromatic keyboard, offering us the luxury of ascending and descending in half note steps. If we did so between two C keys an octave apart, the result would be:

Ascending : C C# D D# E F F# G G# A A# B C

Descending : C B Bb A Ab G Gb F E Eb D Db C

That’s a thirteen note sequence. And, just in case you’re wondering, yes C# is the same note as Db on a chromatic keyboard. This aspect of musical theory is called enharmonics; two names for the same note. Knowing exactly how, and exactly when to use each, is complicated theory we will save for a rainy day. On diatonic harmonicas, and on a bandstand however, you’ll normally hear the notes of the chromatic scale referred to as follows:

That’s a thirteen note sequence. And, just in case you’re wondering, yes C# is the same note as Db on a chromatic keyboard. This aspect of musical theory is called enharmonics; two names for the same note. Knowing exactly how, and exactly when to use each, is complicated theory we will save for a rainy day. On diatonic harmonicas, and on a bandstand however, you’ll normally hear the notes of the chromatic scale referred to as follows:

Common use : C Db D Eb E F F# G Ab A Bb B C

How to crack the modal code

Let’s return to our imaginary diatonic, or white key, piano for a moment. To break the routine of the C major scale outlined above, we could experiment by ascending and descending between other like-notes an octave apart; D to D, or E to E for example. In doing so, we would be entering the magic kingdom of modal scales. Tabbing them for the 10 hole harp in sequence from C, the result is displayed in the chart below left. Take some time now to play each line left to right and right to left (up and down) a few times on your C harp. Listen carefully to the end product in each case and note the different character, or flavour, of each scale. How does each one leave you feeling? Can you find any useful or interesting musical licks? Do any of the scales remind you of tunes you have heard before?

C 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B

C 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B

D 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B 8D

E 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B 8D 8B

F 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B 8D 8B 9D

G 6B 6D 7D 7B 8D 8B 9D 9B

A 6D 7D 7B 8D 8B 9D 9B 10D

B 7D 7B 8D 8B 9D 9B 10D 10B

Now let’s analyse what’s actually happening by mapping out the musical steps, or intervals, we’re making in each case. Referring to the chromatic piano keyboard pictured above right will help you visualise what’s happening. We’ll call a whole-tone step T and a half-tone (or semi-tone) step s.

C T T s T T T s C D E F G A B C

D T s T T T s T D E F G A B C D

E s T T T s T T E F G A B C D E

F T T T s T T s F G A B C D E F

G T T s T T s T G A B C D E F G

A T s T T s T T A B C D E F G A

B s T T s T T T B C D E F G A B

And this is almost all you need to know – it’s that hard! In the left hand panel above, you can see how the semi-tone steps shift to the left each time we move up a mode. These are the intervals between E and F, and B and C. The right hand panel demonstrates this too. The semitone shifts are what changed the ‘flavour‘ of the modal scales you played earlier. They move closer to the start note each time you move up; until they eventually become the start note.

modal scales you played earlier. They move closer to the start note each time you move up; until they eventually become the start note.

Name and shame

I’ve used the term ‘flavour‘ with some forethought. I could have used ‘mood‘ but I don’t want to confuse this with mode, so let’s stick with the cooking metaphor for now. In which case, just as we’ve given each tone a letter of the alphabet, so each of the diatonic recipes above, or modal scales, has a given name (in green):

C T T s T T T s Ionian

D T s T T T s T Dorian

E s T T T s T T Phrygian

F T T T s T T s Lydian

G T T s T T s T Mixolydian

A T s T T s T T Aeolian

B s T T s T T T Locrian

These are the ancient Greek names attributed to each mode by Pythagoras. Yes the mathematician. You know folks sometimes say music and maths have a lot in common? Well right now you’re at the heart of the matter. The Greeks recognised the science, art and magic of music. Indeed, music was actually part of the ancient Olympic Games.

These are the ancient Greek names attributed to each mode by Pythagoras. Yes the mathematician. You know folks sometimes say music and maths have a lot in common? Well right now you’re at the heart of the matter. The Greeks recognised the science, art and magic of music. Indeed, music was actually part of the ancient Olympic Games.

Pythagoras used musical traditions from remote areas of the known world to describe the character of each mode. The Dorians were one of the four major Greek tribes and came from central Greece – they built temples with plane looking, Doric, capitals to their columns. Locrians were a minor tribe from north-west mainland Greece. Two of the other major Greek tribes were the Ionians who settled the Ionian seaboard in what is now Turkey, and the Aeolians, originally from Thessaly in mainland Greece. The Phrygian community was from Asia Minor (Turkey), as were the Lydians of Anatolia. Mixolydian means half, or almost, Lydian, and is a technical afterthought rather than an actual Greek tribe of small stature.

Nouvelle cuisine

Relating each of the modal scales to parts of the known world made the ‘flavour‘ of the mode more meaningful to the Greek listener. In the post-modern world we might call Phrygian the Spanish or Moorish mode, Lydian the Scottish mode, Aeolian the Klezmer or Yiddish mode and Dorian the English Folk mode. Meanwhile, philosophers ancient and modern might describe the ‘feeling‘ or ‘mood-changing‘ effect of each mode in the following way:

Ionian Harmonious or tender

Dorian Serious or melancholic

Phrygian Mystic

Lydian Happy or vibrant

Mixolydian Angelic or youthful

Aeolian Sad or tearful

Aeolian Sad or tearful

Locrian Wistful or yearning

Getting real with it

Now that the underlying theory is clearer, one glaringly important question arises; what practical use is there for musical modes while playing the diatonic harmonica? The answer in one word is, lots! But first let’s translate everything into harp speak.

To start with, it’s useful to equate each mode name with a standard key name. We’ll then need to agree a useful root note, or start point, for each key; officially called the point of resolution. Finally, it helps to find a memorable tune we can use as an aide memoire to recall each mode in a practical sense. Using a C harmonica, our shortlist might look like this:

Mode Key Root Note(s) Memorable tune

Ionian C major 4B, 1B, 7B, 10B When The Saints Go Marching In / Buffalo Gals

Dorian D minor 4D, 1D, 8D Scarborough Fair / Drunken Sailor

Phrygian E minor 5B, 2B, 8B Knights in White Satin / Misirlou

Lydian F major 5D, 9D, 2D” Au Claire de la Lune / Price Tag / Simpsons Theme

Mixolydian G major 2D, 6B, 9B Norwegian Wood / Clocks (Cold Play)

Aeolian A minor 6D, 3D”, 10D When Johnny Comes Marching Home / Losing My Religion

Locrian B diminished 3D, 7D She’s A Rainbow

Running around in circles

Some of you may be thinking this is all very user-friendly, but you’d really like to get some engine oil under your fingernails. OK, roll your sleeves up, it’s time to haul the whole thing onto the inspection ramp. To truly relate the concept of modes to the 10 hole diatonic harp, we have to embrace a pivotal subject of musical theory. It’s one that can quickly cause harp playing eyes to glaze over; the circle of fifths (or positional playing). Trust me when I say it’s really quite simple. If I can get it, so can you. Let’s gently set the ball rolling using a C harp.

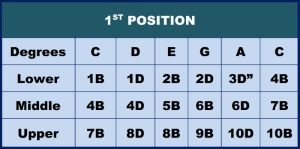

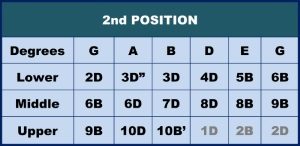

We know we can play any number of straight harp tunes, including When The Saints Go Marching In, from 4B right? We also know this is called 1st Position (Straight Harp). Well, to put it politely, these tunes soon feel pedestrian. We want to rock it up and play like Little Walter. So we find ourselves flipping through pages until we come to Cross Harp, where we adopt 2D as our root and range up and down between it and 6B. We then start to investigate draw bends.  As we do so, we’re probably aware that we’re playing in G major. We also know this as 2nd Position.

As we do so, we’re probably aware that we’re playing in G major. We also know this as 2nd Position.

But let’s revisit what just happened for moment. To reach G from C, we’ve ascended 5 degrees, or notes, of the major scale. If we wanted to use posh musical vocabulary, we could call this a diatonic interval of 5. We’ve gone from C, through D E F up to G in 5 steps. Remember that we include the root note of C as step 1 when we start counting. It’s like the working week from Monday to Friday – five days in all. Hold that thought.

Step back baby, step back

Stepping back into modal terms for a moment (and once again if I can do this, you can too, so stay with it), we’ve moved from Ionian (C) in root note 4B, to Mixolydian (G) in root note 2D. Et voila! It’s that simple. We’ve worked our way from 1st to 2nd position, from 4B to 2D, from Ionian to Mixolydian and it’s all making sense. Ready for the next step?

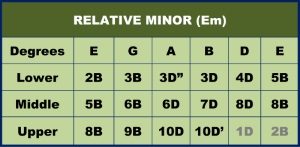

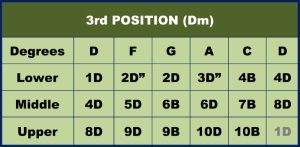

If we counted up another interval of 5 from G, we’d reach D and that would be Dorian mode. Which is 3rd position from 4D. Hold up the fingers and thumb of either hand and count this out across your digits: G A B C D. You just used your naturally patented, circle-of fifths, double-checking system. Take it with you wherever you play. By the way, to be absolutely accurate, we actually found D minor. We won’t explain the reason for this right now, as it will interrupt our line of thought. But once you’ve finished this page, had a massage and finished a cold glass of whatever takes your fancy, you can check it all out here.

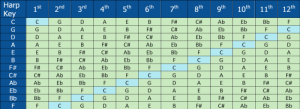

Back on message. Position-wise, we can keep going round the circle of fifths using our fingers and thumbs until we eventually return to C. In doing so, we will have covered all twelve degrees of the chromatic scale. Or will we? I hear some of you asking ‘how come, when counting round in intervals of 5, it takes us from C to G, G to D, D to A, A to E, E to B, B to F and finally from F to C? That’s only 7 notes on the keyboard, not 12!‘.

Better by half

Here’s the answer. To be empirically accurate, we need to start counting not in diatonic intervals, but in chromatic intervals, or half steps only. This way the chromatic interval between C and G is 8 half-step degrees, instead of five diatonic steps.The keyboard image above will help you visualise this. The chromatic interval from G to D is also 8 half-step degrees. Only now, when we continue counting chromatically, do we actually cover all 12 degrees of the chromatic scale using the white and black keys of our piano keyboard. Let’s check it all out, ascending in 8 half-step intervals from C:

Here’s the answer. To be empirically accurate, we need to start counting not in diatonic intervals, but in chromatic intervals, or half steps only. This way the chromatic interval between C and G is 8 half-step degrees, instead of five diatonic steps.The keyboard image above will help you visualise this. The chromatic interval from G to D is also 8 half-step degrees. Only now, when we continue counting chromatically, do we actually cover all 12 degrees of the chromatic scale using the white and black keys of our piano keyboard. Let’s check it all out, ascending in 8 half-step intervals from C:

C G D A E B F# Db Ab Eb Bb F

Well done. Here you have an absolute DNA blueprint for all twelve positions on a C major diatonic harmonica. You can take this same 8 half-step formula, apply it to any key of diatonic harmonica, and work out its integral twelve positional note names.

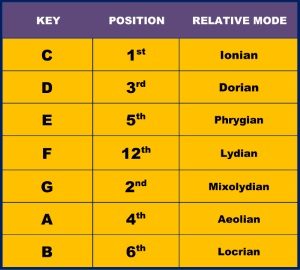

At the same time, you can confidently accept that you’ll encounter our seven modes as you go (in bold above). The modal positions also happen to be the most practical of the twelve options available to diatonic harp players – 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th and 12th – as the root note is not always hidden in an inconvenient bend. Now, just to round everything off, here are the 7 modes again with their root notes and corresponding position on the harmonica, again using a C major harp.

Mode Key Root Note(s) Harp Position

Ionian C major 4B, 1B, 7B, 10B 1st position

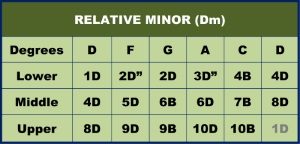

Dorian D minor 4D, 1D, 8D 3rd position

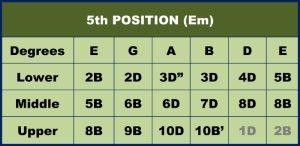

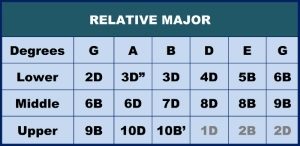

Phrygian E minor 5B, 2B, 8B 5th position

Lydian F major 5D, 9D, 2D” 12th position

Mixolydian G major 2D, 6B, 9B 2nd position

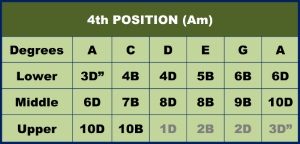

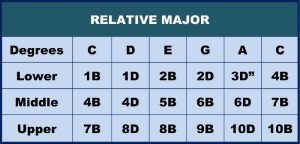

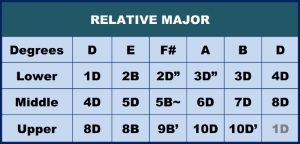

Aeolian A minor 6D, 3D”, 10D 4th position

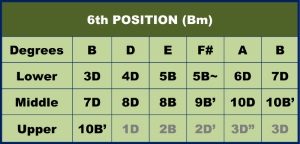

Locrian B diminished 3D, 7D 6th position

Welcome to the human race!

If any of this is page unclear, it’s probably because you’re human, or else you’ve been playing your harmonica instinctively. The message is, it’s time to start playing smart as well as hard, so review the information above and add it to your arsenal. We guarantee it will help shape you into a musician. Very soon you’ll be surprising those who assumed you were just the harp playe’. Now re-read this page until you can comfortably do it all yourself. Then tell all your harp friends where you found the inspiration.

To open up the sound of the major pentatonic on your harmonica (and yes there is a minor pentatonic; it’s the blues scale with the middle note missing), simply play the major scale from

To open up the sound of the major pentatonic on your harmonica (and yes there is a minor pentatonic; it’s the blues scale with the middle note missing), simply play the major scale from